Hats off to John Fox as well for his contributions to Parts 1 and 2 of the DEAMcon23 recap as Cyndi obviously could not be in two places at the same time, and he picked up the additional sessions as needed!

We hope you enjoy this final post recapping this year’s DEAMcon23 Special Edition of the DirectEmployers Week In Review.

Candee J. Chambers, Editor-In Chief

Bios on the presenters are available here.

- ADA Update: Fast-Breaking Developments on “Reasonable Accommodation”

- A Conversation with ODEP Assistant Secretary Taryn Mackenzie Williams

- OFCCP Ombuds Stergio Discussed Using His Office to Assist with OFCCP Conflict

- Research Team Illustrated How Career Pages Design Can Make a Difference in Increasing Applicants with Disabilities

- DEAMcon23 Ends with a Bang After 27 Presentations

ADA Update: Fast-Breaking Developments on “Reasonable Accommodation”

Five Magic Words: “How Can I Help You?”

Despite all the recent new developments in this area of the law one thing that has not changed “is the question that a supervisor or a manager or HR professional or an EEO professional should ask when an employee comes into the office and says I’m having trouble doing something because of some condition,” David advised. Those “five magic words” are “How can I help you?”

“[T]here might be some quick simple lazy fix – and you don’t have to get into ADA land, analyzing disability and qualified and reasonable accommodations,” he pointed out. “There really might be a quick simple solution.”

In such situations, David offered an example and recommended documenting the following six things:

- what the worker said initially. Example: “I’m having trouble interacting with the public because of my anxiety.”

- that the supervisor/manager/HR/EEO professional said “How can I help you?”

- the worker’s response. Example: “I need a break for a few minutes every couple of hours.”

- that the supervisor/manager/HR/EEO professional said “Okay.”

- that the supervisor/manager/HR/EEO professional didn’t ask for anything medical. “You want to keep your supervisors and managers out of medical stuff,” David noted. “You want them focused on performance. So, this is your chance to document that they didn’t ask anything medical.”

- the follow-up. Employers often forget to do this part, David observed. “Whether it’s a day later, a week later, a month later, go back and follow up, and say ‘Is it working?’ because if it’s not working, then reengage in that ‘how can I help you’ step. Only then, “if there’s nothing that’s quick and simple and easy, [do] we get into ADA land.”

What Is, and What Is Not, a Reasonable Accommodation?

“[ADA land] is “where you refer the person over to – whether it’s EEO or HR – whomever it is at your organization that does reasonable accommodation issues,” so they can go through with the interactive process to arrive at a reasonable accommodation, David explained. A reasonable accommodation is “removing some workplace barrier so this person can do this job,” David said.

Referencing the 126-page paper he prepared for attendees, David explained that the paper contained all the cases he would cover for the presentation. These selected cases “are really good illustrations of the points,” he observed.

Does reasonable accommodation mean preferential treatment? “Courts have said ‘yes,’” David reported, noting that the U.S. Supreme Court is among those that have used the term “preferential treatment” (see U.S. Airways v. Barnett, 535 U.S. 391(2002)). “It’s so the person can have a level playing field. Even though I don’t love the term, it’s kind of useful because it points out to supervisors and managers that you do have to do more for this person than you’re doing for everybody. You’re not changing the rule for everybody. You’re doing something different for this person [so that the person can have a level playing field],” he stated.

Most often, it is a change to policies and procedures. While reasonable accommodations could be changing physical barriers, much more often, it is changes to policies and procedures on when the work is done, where the work is done, how many breaks I get, and how long are those breaks. “I’d have to say 95% of the cases I read and hear about are cases where the person needs some change to a policy or a procedure,” he reported. “Remember, reasonable accommodation isn’t just so you could do the job. It’s also […] so, you can have equal benefits or privileges,” he pointed out.

Covid & hybrid workplaces. With the impact of Covid and hybrid workplaces, an issue that comes up often is what if a worker needs/requests an accommodation both onsite and at home? David asserted that the obligation to provide equal benefits and privileges “means you’ve got to give it in both” if you are allowing hybrid work for everyone else. “There are no cases on this yet, but you don’t want to be that case.”

Undue Hardship

“We’ve got to give a reasonable accommodation unless it causes undue hardship,” David said. On that point, he advised, “[y]ou never want a supervisor or manager to say that [a proposed reasonable accommodation] is “not in [the] budget.” Because if an employer does that “then you just opened the door in litigation for somebody who sues you to find out all the places you spend your money. And money doesn’t win. I don’t know of a single Court of Appeals case over the last 30 years where an employer has won saying something was too expensive.”

Rather, winning arguments are those where employers assert they would suffer undue hardship due to the effect something has on other employees, he said. For example, other employees would have to work much longer or harder. “Teach [your supervisors and managers] not to say it’s not in my budget, even if it’s not,” David recommended.

There may also be situations where the provisions of an applicable collective bargaining agreement render an accommodation request an undue hardship. In those cases, employers should at least try to negotiate with the union, he suggested. “But if the union just says no, what do you do? Document. You tried, [but] the union said no. And I’ve had EEOC investigators say they’ll leave you alone and go after the union if that’s what happens,” he reported.

What Does “Reasonable” Mean?

The definition of “reasonable” is important because “[i]f something is not a reasonable accommodation to begin with, you don’t have to prove it’s an undue hardship,” David explained. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”), “reasonable means it is effective, it works, and it lets this person perform the job in a satisfactory way,” David said. Turning to relevant court decisions, he noted that when an employee tells an employer that a specified accommodation is not even an option, then it is not reasonable, meaning the employer does not have to offer it. Again, it is vital that the employer document such a conversation, he emphasized.

Where an accommodation “is consistent with an employee’s doctor’s note,” that is reasonable, courts have ruled. “[F]rom a best practices perspective, I think that really means that you need to have these discussions with […] the treating physician, about possibilities, alternatives, [and the parameters of what is, and what is not, helpful]” David recommended. In addition, where an accommodation is medically necessary, it’s reasonable. However, if a worker brings in a doctor’s note that says s/he can return to work with no restrictions, that’s not a reasonable accommodation issue.

Components of the Interactive Process

“[I]n probably 95 percent of the cases,” the interactive process starts with the worker asking for something, David noted. Generally, the worker must articulate the accommodation request to the employer “because [the ADA] is an empowerment statute,” David said. “Now, if you know about the condition, and you know the person needs something, then that’s a little different.” In those types of situations, the employer “should be proactive.” That means asking, “How can I help you?” “That counts as the first step in the interactive process,” he said.

Futile gesture doctrine. When a supervisor/manager says something along the lines of “we don’t do anything for anybody. We follow the rules for everyone. We make no exceptions,” that opens “the door to what courts have called the futile gesture doctrine,” David warned. Add “we make no exceptions to a rule” to your list of things to train supervisors not to say, David advised. Of recent relevance are situations where, in the COVID context, “people are being brought back to the workplace and the higher-ups are saying ‘everybody must be back in the workplace,’” David observed. That likely opens up the futile gesture doctrine, he said. “[Y]ou [must] explain to supervisors [that] exceptions have to be made if the person has a disability, needs the accommodation, [and] can do […] the essential functions of the job with that accommodation,” he told the audience.

What exactly does a worker have to say to start the interactive process? While there is no “magic language” workers must use, they do have to communicate enough to give the supervisor, manager, or reasonable accommodation coordinator, information to know they need something or are having trouble doing something because of a condition that could be a disability. I’m needing something or I’m having trouble doing something. This is the standard I use.

Generally, mere complaining does not trigger the interactive process unless the worker ties the complaint to an inability to do something because of a condition that could be a disability.

Requests through third-party FMLA administrators. When an employee states they need Family and Medical Leave Act (“FMLA”) leave due to the employee’s condition that may be a disability, it is a best practice for the employer to consider that request as triggering both the FMLA and the ADA interactive process. In contrast, if an employee seeks leave because of a family member’s condition, that is only FMLA, David clarified. He then alerted the audience to the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals’ (Cincinnati) 2022 decision in King v. Stuart Trumbull Memorial Hospital, Inc. There, the Sixth Circuit concluded that even though an employee’s leave requests went to a third-party administrator, that triggered the ADA interactive process. “What that means is you’ve got to train your third-party administrators to work with whoever does ADA when something like that comes in,” he cautioned.

Insulate managers and supervisors. Employers’ documentation of the interactive process needs to be thorough and detailed. “Document it like it’s minutes of the meeting,” David recommended. Moreover, it should not be the supervisor or manager handling the details. Rather, it should be HR or the organization’s reasonable accommodation coordinator. Employers should “insulate [the] supervisor and manager, the decision-makers who are making the decisions about this person’s work product or making the decisions about this person’s job duties. You don’t want them to be doing this interactive process,” he said.

Two-way street. Remember, both the courts and the EEOC have said that the worker must cooperate with the employer, David pointed out. Moreover, the worker must give the employer updated information. “Most of the ADA cases are not obvious disabilities,” he noted, adding that the top three conditions in ADA cases are back impairments, mental health impairments, and neurological impairments. In such cases, “[the worker] cannot just insist on one particular accommodation to the exclusion of a discussion of anything else. That’s not cooperating,” he said.

Employer gets to choose among multiple, effective accommodation options. If the interactive process arrives at more than one accommodation that works, the employer gets to choose which one to implement, according to both the courts and the EEOC. “It doesn’t have to be the one the person wants. It doesn’t have to be the most beautiful. It just has to work,” David said.

Addressing coworkers’ questions. When addressing coworkers’ questions about an accommodation situation, employers must be careful not to disclose a worker’s medical information. “The best approach is to say something like, ‘This is private information, and I can’t share it with you. And I wouldn’t share your private information with somebody else,’” he suggested.

Types of Accommodations

David wrapped up by going over several types of accommodations:

- (Unpaid) Leave – Factors in determining whether leave is a reasonable accommodation include the amount of time and whether the request would cause the employer an undue hardship. The answers to those questions generally depend on the position involved. The difference between FMLA leave and leave as an ADA accommodation is that for ADA accommodation, the employer must keep the same position open (unless it is an undue hardship). In contrast, for FMLA leave, the employer need only provide the returning employee the same or equivalent position. Thus, leave as an ADA accommodation is “more protected than FMLA [leave],” he pointed out. While indefinite leave is not a reasonable accommodation, employers may have to probe into what the worker and relevant healthcare providers are asking for to ensure that the request is actually indefinite.

- Job Restructuring – While job restructuring can be a reasonable accommodation, employers never have to sacrifice the job’s essential functions.

- “Doing a Nice Thing” – If an employer relaxes some essential functions temporarily, will that hurt an employer’s argument as to the function being essential? “Almost all of the courts say no, you don’t get punished for doing a nice thing,” he stated. However, he recommended that employers document that: (1) all parties understand that X, Y, and Z are essential functions of your job; (2) per the worker’s request, the employer is waiving X essential function; (3) the waiver is temporary, based on the employer’s discretion; and (4) if there is a performance review that comes up during this period, make sure that supervisor documents that we haven’t been requiring the worker to do one or more essential functions.

- Transitional Duty/Light Duty – Generally, employers don’t have to create light duty assignments that don’t currently exist. “If you’re going to create them, you can do it for a temporary time period, […] but still document those same four things [listed in the item above].

- New Supervisor – “Courts are saying you don’t have to change somebody’s supervisor as an accommodation, but you might have to change supervisory techniques,” he reported.

- Providing a Job Assistant – While providing a job assistant, such as a reader or an interpreter, might be a reasonable accommodation, having someone do the job functions for the employee is not.

- Rescinding Discipline – If the employee tells the employer about a possible ADA-covered disability before discipline is implemented, then rescinding discipline could be a reasonable accommodation. “We’re looking prospectively,” he pointed out. It’s important to also keep in mind that “there are cases that say not giving somebody counseling, maybe because you feel sorry for them, is evidence of discrimination.” Accordingly, David reminded the audience of the “Five Magic Words: How Can I Help You?” On this point, it is important to “explain to supervisors [that] honest, accurate performance reviews are part of not discriminating against somebody because you’re letting them know where they need to improve. You’re letting them know where they might need to be asking for an accommodation,” he advised.

- Work-From-Home – When an employee requests working from home as an accommodation, employers must evaluate several key questions. First, “does the person have a disability?” Second, “does the person need to work at home because of the disability?” That is where questions of medical necessity and alternatives come into play. Third, “Can this job be done at home?” For example, jobs that require in-person interactions with the public or handling of confidential information/documents cannot be done at home.

- Modified Work Schedule – The key question when an employee requests a modified work schedule is whether the shift is an essential function. “This is where we have just a divergence between what EEOC says and what courts say,” he noted. “The EEOC says shifts are not essential, so you must modify the shift unless it causes an undue hardship. Courts, […] generally say shifts could be essential.”

- Fragrance-Free Environment – The “EEOC says a totally fragrance-free requirement is not a required accommodation because it’s not even reasonable,” he noted. “But if it’s just one smell, that could be different,” such as in situations where a worker has a severe allergy.

The Accommodation of Last Resort: Reassignment

“If nothing else works, don’t forget to look for reassignment,” he recommended. “What is reassignment? […] it’s looking at vacant, equivalent jobs, and if nothing vacant and equivalent, then vacant lower-level jobs,” he explained. Reassignment “is the accommodation of last resort, [but,] you don’t have to bump or promote somebody, [there] has to be a vacancy.” However, reassignment is only an option for a worker who has been in the job and cannot do it anymore. The reassignment also must be a job the worker is qualified to do.

The trickiest reassignment question is: “What if [the worker seeking reassignment] is not the best qualified [compared to others seeking to fill the vacancy]?” Unfortunately for employers, the EEOC, the Department of Justice, and most federal courts of appeals say the position needs to go to the ADA-protected employee seeking the accommodation. Yet, “there are some cases that now go the other way. – […]more and more courts of appeals are now holding the other way.”

A Conversation with ODEP Assistant Secretary Taryn Mackenzie Williams

David Fram’s presentation just prior was a useful building block for Candee and Taryn’s discussion about Diversity, Equity, inclusion, and Accessibility (“DEIA”) and they referenced it repeatedly throughout. Both agreed that David’s suggestion of asking a worker “How Can I Help You?” is a great approach for arriving at accommodations, even for workers with the same medical conditions, because every worker’s situation is unique.

How Does ODEP Work with Employers?

“We don’t have enforcement authorities. We are not EEOC. We are not OFCCP. We’re not enforcing Section 503, for example. But we are often that agency and that entity that brings its subject matter expertise to bear on the barriers that individuals [with disabilities] are facing as they seek employment. So much of our work is done through collaboration […] seeking to influence best practices,” Taryn explained.

“[…] One of the ways that we do our work is through our technical assistance centers,” she pointed out. For example, “the Job Accommodation Network [“JAN” is] free, confidential, expert technical assistance and guidance that individuals, employers, or employees alike can receive around accommodations.” Another example is the Employer Assistance and Resource Network on Disability Inclusion (“EARN”), which offers information and resources to help organizations recruit, hire, retain, and advance people with disabilities; build inclusive workplace cultures; and meet DEIA goals.

Self-ID Concerns, Leadership, & Disclosure Benefits

“[E]mployees with disabilities face the risk of stigma. They are unfortunately rightfully concerned that disclosing could result in firing or being treated – not being hired or being treated differently by their peers or by their supervisor,” Taryn acknowledged.

However, “[t]here also can be […] benefits to disclosing on the job,” she said. “There are opportunities to join a broader network of colleagues who are also individuals with disabilities and certainly best practice that we often see is the creation of affinity groups for people with disabilities and individuals who have loved ones with disabilities,” she pointed out. Peer mentors can help a worker understand how to request accommodations, Taryn noted. Moreover, they can help their fellow workers with disabilities “understand that yes, there is stigma, but there is also power in embracing your full self.”

Both Candee and Taryn highlighted the importance of an organization’s leaders disclosing their own disabilities. “It can make such a difference, Taryn observed. Expanding on her personal experience, she continued:

“It creates an environment where I don’t feel like I have to mask all of who I am. I’m showing up fully to work. And I am saying to my peers and to my colleagues that, you know what? We are figuring this out in real-time. Like what does it look like to create an environment where people with disabilities are truly included and can thrive? And we don’t always have the answers, but we are building that knowledge together, especially now, especially now when our workplaces are transforming so quickly. When there’s a tension between returning to normal and embracing the new reality, I think it’s so important that we as leaders stand up and we identify and we communicate to employees what those benefits can be, and also be candid about what those risks are and the steps that we’re taking to mitigate those risks, like providing training on disability etiquette and awareness, like providing training on what it means to provide accommodations in the workplace.”

Accommodations & Disability Inclusion

“Don’t make the accommodations process hard,” Taryn urged the audience. “Don’t bury it on your intranet. Don’t bury it on your career pages. Don’t leave an employee or job seeker or applicant who’s coming to your site confused or dissuaded from being a part of your organization because they can’t figure out how to request those accommodations.”

“It just doesn’t make good business sense to leave talent behind,” she remarked. “And that means ensuring that [employers are taking steps] to ensure that folks know that they can apply to your jobs, that they will be welcomed at your jobs.” ODEP and its sponsored organizations “have tools and resources to support this,” she pointed out. “JAN has an accommodations toolkit [that is] a guide to help you in thinking through how to set up best practice accommodations policy so that your employees and job seekers aren’t left wondering what this process looks like,” she said.

“In the DEIA space [“Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility”], sometimes we increasingly hear DEIAB,” with the “B” standing for “the sense of belonging,” Taryn added. Belonging is not only important for recruitment, hiring, and the initial accommodations processes, but it is also important to ensure “that at every step in someone’s career, recognizing that disabilities evolve, that they know what they can do to access accommodations. That is so important. That contributes to the belonging.”

What Are ODEP Investments That Support Employer Efforts to Increase Disability Inclusion?

One-way ODEP supports employer efforts to increase disability inclusion is to foster registered labor apprenticeships as a pathway to careers, Taryn reported. “PIA, Partnership on Inclusive Apprenticeships is working to increase the number of people with disabilities who have access to apprenticeship opportunities and those high growth [opportunities], including nontraditional, sectors. […] That also becomes very important as we think about infrastructure spending.” One lever to affect change is thinking about “how do we leverage those investments to make sure people with disabilities are a part of that, and apprenticeships and [their] funding [are] a key part of that.

Another way is accessible technology, she continued. One of ODEP’s technical assistance centers is the Partnership on Employment & Accessible Technology (“PEAT”), which fosters collaborations in the technology space that build inclusive workplaces for people with disabilities, Taryn noted. PEAT works with the developer community, institutions of higher education, and government agencies to build new and emerging technologies that are accessible to the workforce by design. She said she is particularly excited about the work they’re doing now with artificial intelligence and virtual reality.

“I don’t pretend to be an expert in these issues, but I do know they have significant implications for people with disabilities and the extent to which these technologies and their use pose risk, pose risk for deepening the barriers that exist, deepening the inequities that may exist in recruitment, hiring, advancement, and retention,” she commented. Therefore, “it is important for us to continue to provide support to entities like PEAT and their work in convening those thought leaders and ensuring that we are not forgetting people with disabilities as we develop technologies.”

Subminimum Wage

ODEP is also “very much focused on advancing competitive integrated employment,” Taryn reported. “This is an issue where the President has been clear and very explicit that he wants to phase out [the] subminimum wage. We work very closely with our colleagues within the Department of Labor and our Wage and Hour Division but also with national and local providers all across the country to ensure that we’re providing support to help individuals transition from subminimum wage into competitive integrated employment.”

Inclusive Recovery from the Covid-19 Pandemic

Candee pointed out, and Taryn agreed, that we do not even fully know yet what Long COVID is or what the long-term effects will be. The Biden Administration is taking a “whole of government approach” with the White House and the Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) leading the way in terms of critical research to understand the nature of Long Covid and to support individuals who are experiencing it, Taryn said.

“There are some estimates that anywhere from 7.7 million to 23 million people are experiencing Long COVID. There are also estimates that suggest that up to a million folks are out of the labor force due to long COVID,” Taryn reported. The disability community has “been sounding the alarm for some time that we need to think about […] the implications of [COVID] being a mass disabling event,” she stated. As we continue to better understand Long COVID and the extent to which it will impact the workplace, “JAN is so critical here,” Taryn commented. “Long COVID might be new, but the expertise [JAN has in addressing accommodation concerns] is not new,” she pointed out. When employers go to JAN, they will “find resources that build on [JAN’s close to] 30 years of expertise.”

Both the HHS and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) have issued guidance with a working definition of Long COVID, but that definition continues to evolve, Taryn said. Employers need to understand that employees might be coming to them for accommodations, and again, employers need to not make that hard. “Because we don’t want to lose that talent. And they certainly don’t want to lose their lives and that which makes them thrive,” she added.

What Strategies Can Federal Contractors Implement to Improve Career Development for People with Disabilities?

“It really is critical that you make disability inclusion part of your responsibilities,” Taryn said. “Don’t silo it to one part or division of an organization or an agency. Think of it as an opportunity to really build a culture where people with disabilities can thrive.”

Moreover, ODEP is “eager to support you in your efforts to build inclusive practices. We are eager to share where we’ve had lessons learned,” she continued. Nevertheless, “you don’t have to come to us, you can also go to your own employees with disabilities. Make sure that you’re including them and make sure that you’re providing opportunities for them to inform your practices and policies on everything,” she recommended. “That could be everything from building the successful hybrid working groups […]to ensuring that your meetings and events are accessible.”

Workplace Mental Health

ODEP’s already existing efforts in the area of mental health were accelerated due to the Pandemic, Taryn reported. She recommended ODEP/EARN’s Mental Health Toolkit as a resource for employers. However, “[w]e know that there’s so much more we can be doing and should be doing to support employers and employees alike as we grapple with the ongoing mental health crisis,” she acknowledged.

Taryn also mentioned the Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee (“ISMICC”). The ISMICC reports to Congress and federal agencies on issues related to serious mental illness and serious emotional disturbance. This committee is working on recommendations to address serious mental illness. In addition, ODEP’s Advancing State Policy Integration for Recovery and Employment (“ASPIRE”) Initiative) works with state agencies to advance the Individual Placement and Support (“IPS”) model. IPS is an evidence-based supported employment model for people with serious mental health conditions.

“This is not one of those areas where we don’t know what works,” Taryn asserted. “We know what works. What we haven’t figured out is how to ensure we’ve got funding for what works. So some of the work of ASPIRE is advancing bending, breaking, the sequencing of funding to support IPS models and having states work with each other […] to do model [Memorandums of Understanding] to support more IPS for individuals with serious mental illness in their states.”

Conflict with Full-Time Employment & Disability Benefits

Candee mentioned a stellar job candidate who could only work part-time because she would lose her Social Security disability benefits if she worked full-time, and she noted that this was an example of one difficulty federal contractors encounter in attempting to hire workers with disabilities. “So, what do we do?” she asked.

“We need more voices from outside the government amplifying this issue,” Taryn urged. “It’s important for employers to speak up and educate policymakers on the very real crisis they’re facing. We’re looking for talent. We’ve identified talent but we actually can’t bring that talent on board because of this structural issue.”

Taryn noted that the National Center on Leadership for the Employment and Economic Advancement of People with Disabilities (“LEAD Center”), one of five ODEP-sponsored policy development and technical assistance resources, is working on this issue. “I think when you have the disability community and employers coming together, that is where we’ve actually seen change. That’s where we’ve seen policy get through […]. That’s what I think it will take here. But without that, we’ll continue to find structural challenges.”

OFCCP Ombuds Stergio Discussed Using His Office to Assist with OFCCP Conflict

What is an Ombuds?

Marcus serves as an independent, impartial, and confidential resource available to all OFCCP employees and stakeholders nationwide, including federal contractors and subcontractors, contractor representatives, industry groups, law firms, worker rights organizations, and current and potential employees of federal contractors and subcontractors.

As an external ombuds, he serves as an informal facilitator of disputes between the agency and stakeholders, observes and analyzes trends, and promotes broader conflict competence among OFCCP and the stakeholder community. “I’m facilitating between the agency and any type of external stakeholders who have an interest in the work of OFCCP,” he said.

Background on the Office

OFCCP developed the Ombuds Office in 2019 due to two impetuses:

- A 2016 GAO Report, entitled “Strengthening Oversight Could Improve Federal Contractor Nondiscrimination Compliance” and;

- OFCCP’s 2018 Town Hall Action Plan (see the DE OFCCP WIR story here).

As a result of these two impetuses, OFCCP wanted to enhance communication with stakeholders and increase transparency, Marcus explained. “I came in to create this external Ombuds Office that could do just that, give people a platform to kind of reach out to OFCCP and raise communication or transparency or really any other issues when you might not otherwise do that out of a fear of what happens if you do reach out with complaints about the agency.” In addition, “OFCCP staff are able to contact me if they’ve identified ways I can help them in their coordination with an external stakeholder,” he noted.

Ombuds Standards of Practice

Marcus explained that he follows four standards of practice from the International Ombudsman Association. These are confidentiality, impartiality, independence, and informality.

Confidentiality. While some people think of ombuds as largely mediators “very seldom am I actually mediating,” Marcus clarified. “Sometimes people just want an individual private conversation.” He also explained that he can share, or not share, all or part of a conversation with specified parties as requested.

Impartiality. Even though Marcus is an OFCCP employee, he is “a neutral third party who doesn’t take sides.” He elaborated: “I don’t direct outcomes in favor of external stakeholders or OFCCP because it’s not in my interest to do so. If I were to do so, people wouldn’t trust me and then I wouldn’t have anybody contacting me and then I probably wouldn’t have a job.

Independence. Marcus’ role is not part of any other division in OFCCP. “I don’t participate as part of any other work teams or divisions or offices within OFCCP except for the Ombuds Office. So, I don’t align myself more closely with particular people or divisions of OFCCP than I do others, or that I do with external stakeholders. And that allows me to maintain that impartiality and also confidentiality,” he explained.

Informality. “I don’t conduct investigations,” Marcus noted. “If you reach out and say this person I feel like is doing things all wrong according to the regulations, I can’t initiate an investigation and then issue a finding where I would say, yep, you’re right, OFCCP, you need to do this differently. I don’t have that authority, and, quite frankly, I don’t want that authority because that would jeopardize my neutrality and also make it complicated for me to maintain confidentiality. […] I can’t replace the person at OFCCP you’re not working well with, but I can step in and informally help you by facilitating a conversation with them.

When Marcus invited questions about these standards, DE Executive Director Candee Chambers noted her past experience working with him. “I have learned he can be trusted,” she said. “I do firmly believe that he’s truly kept every conversation confidential.”

Resolution Techniques

Marcus tracks the types of referrals he receives and looks for trends. Looking at a pie chart based on fiscal year (“FY”) 2022 data regarding the conflict resolution processes, he first noted that about 65 percent of everything he did was working with people one-on-one, i.e., individual consultation. That involves “you reaching out, telling me what’s going on, me providing confidentiality and just being a sounding board, helping you figure out what is best to do in your situation,” he told the audience.

The next largest piece of the pie was “shuttle diplomacy.” He described that as “going back and forth between two parties.” “Lots of times people aren’t ready to be in the same room, whether it’s virtual or in-person, right away,” he observed. “I try not to get people in the same room for let’s say a mediation or facilitated dialogue right away,” he reported. “More often we’re working through shuttle diplomacy where I’m having private calls and conversations with people, relaying messages back and forth.”

“Then […] about 10 percent of the time it does get to mediation because people have made some progress through shuttle diplomacy and maybe want to continue working and see if they can close the gap and come up with something, whether verbally or in writing that works for them.”

Primary & Secondary Issue Types

Again, based on FY 2022 data, Marcus identified several primary issues which are those mentioned when stakeholders first reach out to him. The most cited ones are transparency, extension requests, scope of review, investigation concerns, jurisdiction disputes, negotiation impasse, disputed determination, communication, conduct, personnel, policy and/or procedural concerns, “other,” and need for guidance.

Secondary issues are those underlying the primary issues. Those include communication, transparency, consistency, reasonable time frames, reactive devaluation, efficiency, and collaboration. “Reactive devaluation is a form of bias that basically comes about if we had a tough time working with someone in the past and we have to work with them again, we sometimes subconsciously just devalue the things they say or do,” he explained. “Not because we actually disagree with them or don’t think they’re good ideas or don’t like that person’s processes, [rather], it’s because they came from somebody whom we have negative perceptions of.” To address this situation, “we figure out what it is that could change that makes it easier to work with them.”

Inquiry/Referral Sources

Looking at both FY 2022 and FY 2023 (so far) data, Marcus identified the sources of referrals/inquiries to the office. The most common source is from contractor representatives and complainants, followed by contractors and then OFCCP. “You might be surprised [to see] such a high number [of complainants], he said. “I think this is probably because there are times when a complainant working with OFCCP disagrees with the decision or outcome and [wants to know what is] the next step in the process.” “And the district office lots of times will say there really is no next step,” he continued. “I think they lots of times will give them my information so they can reach out to me, and we can have conversations about what it is they found problematic and what they disagree with. And again, that’s data I can track and either provide back to the district office or more generally inform OFCCP leadership these are some of the issues complainants are experiencing when they’re going through situations with OFCCP.”

“I think initially people thought of me as only working with contractors and I had to work hard to dispel that notion [and clarify that I work] with all angles of the OFCCP community including from within,” he stated.

Although the numbers for FY 2023 so far appear to be low, “I’ve also noticed through my first three years prior to this one, quarter three for whatever reason has been the busiest,” he reported.

Later in his presentation, Candee asked Marcus whether he sensed contractors might hesitate to contact him out of fear that OFCCP might retaliate against them. “I actually wonder if that’s why the number of referrals I get from contractors is lower than contractor representatives who might not share the name of the contractor, or with complainants who feel [that] there’s no harm in reaching out [because their identity is already known to the agency.]”

While he acknowledged that the fear is understandable, Marcus is not aware of anyone who has faced that after contacting the Ombuds Service. Occasionally, individual stakeholders will ask him not to share any part of their conversations with OFCCP. “I think [that] sometimes makes people a bit more comfortable with eventually saying, yeah, reach out to the district office and see where that leads us,” he noted. Also, if a contractor believes a compliance officer is treating them differently after finding out they reached out to [the Ombuds], “then they can go to the district director with those concerns.” “If you don’t get the answer you like from the district director, there’s a regional director above them,” he continued. “You can always loop me back into that because that’s a concern I’d take really seriously.”

Trend Analysis via Annual Reports

At the end of every FY, Marcus puts together an annual report to examine trends. The goal of these annual reports is “for [OFCCP] senior leadership to have the awareness that it needs in order to make changes that address your concerns and the issues you’re experiencing,” he told the audience. “But again, confidentially, without me ever sharing your names, just issues data.”

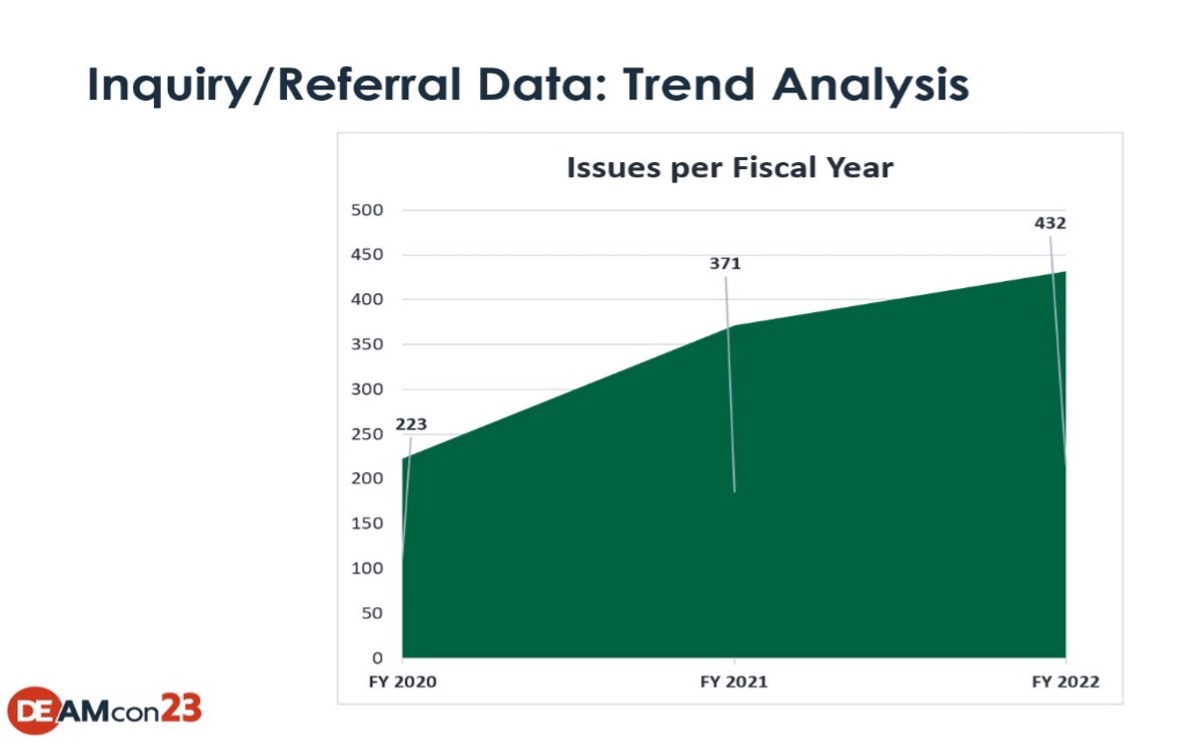

He shared a few charts to illustrate these trends. First, he shared the following chart:

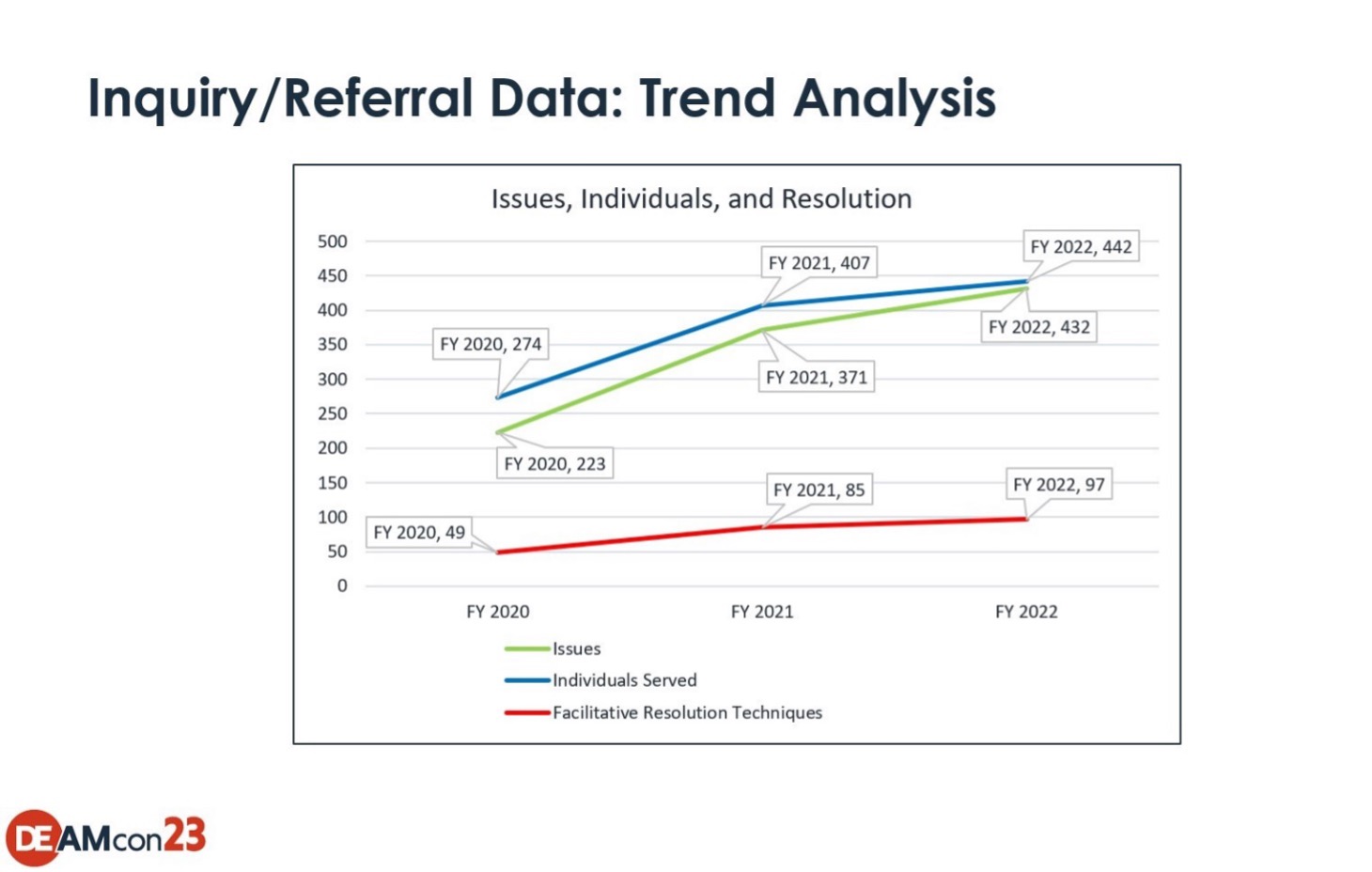

Taking into account that the number of issues has increased from FY 2020 through FY 2023, Marcus said he wanted to dig deeper because it might not be fair to just conclude that conflicts with the agency have increased. Thus, he moved on to the following chart:

The data in the above chart “is the sum of primary and secondary issues” that he identified earlier. The red line, representing facilitative resolution techniques, constitutes “everything except individual consultation” (i.e., it covers shuttle diplomacy and mediated facilitated dialogue). The blue line represents the individuals with whom he has worked. Marcus acknowledged that, as he gained more experience in his role, he is “better able to identify issues.”

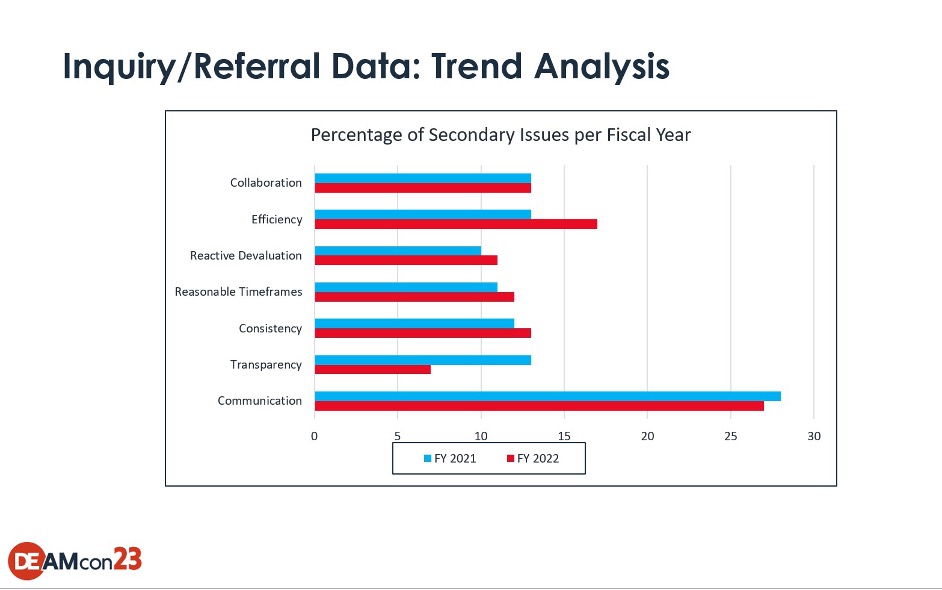

Next, he shared the following chart illustrating trends in secondary issues:

Of particular note were the increases in communication and efficiency as secondary issues. He pointed out that in FY 2021, presidential administrations changed. “New senior leadership team comes in and it takes time for people to identify what was going on at the agency [and what direction they are going to take various policy matters],” he pointed out. “What I was hearing a lot of shortly after the change of administration was just anxiety about what’s going on.” In FY 2022, [t]here were [new and revised] directives issued by the agency. There were more speaking engagements where maybe specific references to initiatives and strategies and directions moving forward.” He added, “I think maybe once the new directives were issued and people felt less anxious because they knew what the priorities were going to be.”

Working with OFCCP Personnel

During the Q&A session, Candee asked Marcus how he has been received by the agency. “I think early on people within the agency probably viewed me as this person who is just this complaint system who is just going to field complaints from contractors and they were all going to be negative about OFCCP,” he replied. “And that I was going to tell their managers, then they were going to be in trouble with their managers. And that was going to affect their performance,” he continued. “To address that, I tried to really work hard to explain that, no, I’m available to help you with the issues you’re identifying too.”

Candee also asked about his approach when he thinks the parties, particularly the agency, should do things differently. “I think in order to be truly impartial, you have to be listening to what the person is saying as opposed to forming your own judgments about them or what they’re saying,” he replied. “Sometimes, however, as I get more and more information, it does raise questions for me that I will pose [in a] nonjudgmental and as neutral of a way as I possibly can, without suggesting what I think they should do differently. But I’ll just say have you or the contractor considered this? And if so, what happened? If you haven’t, then why didn’t you? I’m not the expert, you guys are. But what would happen if we tried this?” He characterized that as “taking an exploratory approach and asking open-ended questions, putting potential options on the table without suggesting people should actually do what I’m proposing.” He added, “I think that feels less threatening to people if I were to say, look, I looked up in the regulations and what you did is totally wrong. I think that’s when people get defensive and do see me as someone who’s partial as opposed to what I’m presenting myself.”

Measuring Success

Candee also asked how he measures success. Due to the nature of his work, he is not always aware of the ultimate outcome of his efforts, Marcus said. However, there is an Ombuds Service Evaluation Form on the office’s webpage that allows stakeholders to provide feedback.

Aside from that, he also gets a sense of accomplishment from when the agency puts out information, such as FAQs, “that it might not have known to put out before because it didn’t understand how much of a knowledge gap there was.” He continued, “I think that highlights the value of people not just sitting there at their desk feeling frustrated […] but sharing them with somebody who can present the data confidentially.”

Contacting the Ombuds Service

Stakeholders may contact the Ombuds Service by calling (202) 693-1174 or sending an email to Stergio.Marcus@dol.gov.

Research Team Illustrated How Career Pages Design Can Make a Difference in Increasing Applicants with Disabilities

Preliminary Research & Key Findings

The research. Sandra explained that the focus of their presentation was research conducted by Cornell University, on behalf of the USDOL/EARN, with the following components: (1) literature review; (2) corporate career webpages assessment of 40 U.S.-headquartered 2019 Fortune 500 companies; (3) focus groups comprised of job seekers and employers (Sandra noted that DE helped them recruit employers for these groups); and (4) survey conducted in 2021of 827 recent job seekers with disabilities. As to the 2021 job seekers survey, Sandra noted “limitation” in that about 75% of the participants had at least some college education, which is a higher percentage than the general population of job seekers with disabilities. Jonathan also mentioned that they had six distribution partners that reached out to their communities for the 2021 survey.

Key findings & takeaways. Jonathan reported that key findings from their literature review were:

- recruitment practices, advertising, and reputation all have direct effects on applicant pool quantity and quality;

- employee endorsements/testimonials can broaden applicant talent pools; and

- some technologies can unknowingly limit talent pools by filtering out qualified candidates with disabilities and other diverse candidates.

Sandra said that as to corporate career pages, the key takeaways were:

- Overall: 70% of companies have a section geared specifically towards hiring veterans and/or veterans with disabilities. Only 20% have a section geared specifically towards hiring people with disabilities.

- Top Leadership Commitment to Disability: 15% have a statement from a senior executive conveying a company-wide commitment to recruitment, inclusion, and/or career development for people with disabilities.

- Disability Hiring Priorities: 25% of companies have a DEI statement that mentions people with disabilities and goes beyond the EEO statement. 20% have existing targeted hiring and recruitment programs or initiatives (e.g., neurodiversity, autism-at-work, disability hiring plans).

- Supports, Accommodations, and Flexibility: 58% have an employee resource group for disability. 73% have specific information about accommodations during the recruitment, application, and interview phase. 38% have information about flexible work arrangements.

- Credible Media and Messaging: 45% of companies show images of employees with disabilities. “We did not search if they were stock images,” Sandra stated. “I hope they were not.”

- Disability-Focused Partnerships and Recruitment: 18% of companies have specific partnerships with community disability employment organizations. 23% have organizational participation in disability-focused recruitment resources.

The employer focus groups results indicated that they need to:

- Understand how to encourage self-identification of disability in the recruitment/application process

- Understand the perceptions people with disabilities have of the organization and how they may impact a candidate’s choice to apply for or take a job

- Know more about the barriers that candidates with disabilities experience in the recruitment/application process

In addition, the job seeker focus groups revealed that certain traits can signal an employer’s degree of disability inclusion. Those traits include:

- visual representation of disability;

- diversity and inclusion statements (beyond EEO statement);

- website accessibility; and

- obvious and easy access to accommodation information.

One aspect of the 2021 survey of recent job seekers explored which elements of career web pages increased a person’s interest “to a great extent” in applying for a job with a particular employer. The results for selected elements showed:

- Flexible work arrangements – the element most often selected by respondents (50.3%)

- Description of work-life balance programs (44.8%)

- Clear explanation of the accommodation request process for applicants (39.8%)

- Diversity and inclusion statement that includes disability (39.7%)

- Description of disability-focused hiring programs (37.0%)

In addition, the survey explored self-identifying as a person with a disability. The researchers found that:

- 4% of respondents mentioned that they have “always/sometimes” been asked to complete a self-identification form in their recent job application.

- 2% of respondents always identify as a person with a disability, and 42.1% sometimes self-identify.

- employers can include elements on their career page that may increase the likelihood of self-identifying as a person with a disability like flexible work arrangements (41.0%), DEI statement/information that includes disability (35.6%), work-life balance programs (31.8%), and disability-focused hiring programs (30.5%).

Sandra also explained that based on their research, she, Jonathan, and their colleagues found that:

- Flexibility and work-life balance practices may appeal to job seekers more generally.

- By proactively offering such benefits, job seekers with disabilities may be less likely to need an accommodation to be able to do their job.

- These types of programs signal an inclusive workplace for mothers, caregivers, people with disabilities, and many others.

- Tailoring career pages with some of this information, employers can potentially increase interest among job seekers with disabilities but also those with multiple marginalized identities.

Implications for HR Professionals, hiring managers, and attracting job seekers

Checklist for Career Pages. Next, they shifted to the implications of their research for employers and those working with employers. They started by presenting their recommended Checklist for Career Pages:

- Content is accessible – “Make sure your website meets or exceeds Web Accessibility Standards,” Jonathan recommended. The two common ones are the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (“WCAG”) and Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which is based on the WCAG, he said. “And this isn’t just traditional web content, but all media such as videos, […], recordings or interactive features,” he advised. Employers should also provide alternate formats as needed (e.g., transcripts), use plain language, provide explicit, clear information that is easy to find, avoid timing candidates and relying on one type of input, and make it easy to communicate with staff (e.g., by email or chat), he recommended.

- Show leadership commitment to disability inclusion – “For example, if a leader attends a disability inclusion event, like this one, include some photos or media from that because that’s going to [indicate to job seekers] that this organization is going to be inclusive for [them],” Jonathan pointed out.

- Use credible messages – “Spotlight employees with disabilities and the employer resource groups on the career page,” Sandra said. “Show what working at the company is like with clear examples and resources,” she added. “Highlight the work/life balance initiatives that the company might have. Include those that are about disability. And provide information about how you support employees with disabilities.”

- Disability hiring priorities are visible – “Make accommodations and supports obvious,” Jonathan said. “Don’t make them hard. Because many job seekers with disabilities need accommodations not just to do the job but even to get to the interview stage. So, you really want to make sure information about accommodations and supports are really easy to find and […] clearly written so people know whom they have to contact and what do they have to do.” In addition, “make sure that you include links to accommodations information throughout the site, and especially on job listings because that’s where people are more likely to look for information. And then once they get hired, on benefits information.”

- Highlight workplace flexibility – “Offer really clear examples on your website” Jonathan recommended. “For example, if you have successful teleworkers, maybe feature them for a testimonial, or if you have alternate schedules, show that.”

- Spotlight partnerships with community-based organizations – “Community organizations can help you find qualified candidates with disabilities, especially if you’re the smaller organizations,” Jonathan advised. “For example, if you need help finding assistive technology, they can help with that. Or if you’re in a rural area and you need help getting to and from work, they can provide assistance through volunteer transportation networks.”

Hiring inclusively. Jonathan provided the following other tips for hiring inclusively:

- Make job descriptions clear, use plain language, and review them for unnecessary standards

- Separate “nice to haves” from essential tasks

- Be flexible – avoid mandating certain ways of doing things where possible (e.g., using a phone or lifting items)

- Consider assessments other than the traditional interview, such as work examples or job trials

- Consider people with employment gaps on their resume

- Ensure modes of communication meet the needs of applicants with disabilities, and offer flexibility (e.g., written instructions rather than spoken)

- Remind candidates and new employees about self-identification multiple times

Checklist for HR, Hiring Managers, and Communications. Sandra then presented the following Checklist for HR, Hiring Managers, and Communications:

- Use social media to recruit candidates with disabilities – “We’ve seen in the survey that [job seekers with disabilities] actually do use social media,” she noted.

- Provide appropriate resources to bridge accessibility/outreach gaps

- Incorporate accessibility into the process for creating online content – for example, when posting a job description

- Frequently audit hiring practices for continuous improvement and inclusivity

- Recognize the importance of early-stage reactions to disability messaging on candidate choices (e.g., application, disclosure/self-identification)

- Gather feedback regularly about the candidate experience with online outreach efforts

Related EARN resources. Finally, Jonathan also provided this list of related EARN resources:

- Online Recruitment of and Outreach to People with Disabilities: Research-Based Practices (PDF)

- Encouraging Applicants with Disabilities: Job Descriptions and Announcements(PDF)

- Disability Outreach and Inclusion Messaging: Assessment Checklist for Career Pages (PDF)

- Company Website Disability Inclusion Messaging: Observations of Job Seekers with Disabilities (PDF)

- Inclusive Branding and Messaging (PDF)

DEAMcon23 Ended with a Bang After 27 Presentations

Chicago was a marvelous host city! Our DEAMcon23 attendees enjoyed the ambiance of the Renaissance Hotel on the river in downtown Chicago. We watched and learned about the latest developments and best practices and discussed together 27 substantive presentations from some of the nation’s best EEO, OFCCP, DE&I, Federal government, Compliance, and Talent Acquisition speakers. A good and educational time was had by all over the three days of this heralded annual conference.

DE Members may view the presentation slides for all the DEAMcon 2023 sessions at this link: https://deamcon.org/slides.