Majority Said Grutter Promised to End Race-Based Admission Practices This Decade

Majority Found Harvard & UNC Also Failed The Prior Grutter Test Which Made Race-Based Admission Practices in Higher Education Temporarily Lawful Under Narrow Circumstances Both Universities Failed To Follow

Part I, below, sets out what the Court held, exactly.

To help you understand and navigate the law at issue in the Harvard and UNC case decision, you may wish to first read this DirectEmployers Blog from last Monday (June 26, 2023) which describes the law and SCOTUS’ five prior race-based admissions preferences case decisions which have led up to last week’s Harvard and UNC cases before the SCOTUS: “The Harvard and UNC Case Decisions Are Coming: What Corporations, Colleges and Universities, and Federal Contractors Need to Know”.

Part II, below, sets out notable quotes of all Justices highlighting their opinions.

The SCOTUS Harvard/UNC Case Decision. It is 237 (8 x 11-inch) pages in length: almost half a ream of paper. The Court combined the Harvard and UNC cases into one single opinion which you may find here. Justice Jackson did not participate in the Harvard decision since she recused herself for ethical reasons (she was on the Board of Overseers of Harvard College, Harvard’s second-highest governing body, before her appointment to the SCOTUS. She indicated at the time of her Senate Confirmation Hearings that she would not participate in the Harvard decision, as a result).

The decisions were 6-2 to reverse Harvard’s winning decision below in the First Circuit Court of Appeals (Boston) and 6-3 to reverse the University of North Carolina’s winning decision below in the federal District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina. You will find Slip Opinions for all six Justices who wrote opinions in the above-referenced hyperlink. A “Slip Opinion” is the informal form of court decision before it is printed and bound in the formal Supreme Court Reporters (a year or two from now) and assigned a formal citation number at which volume and which pages to find the decision. NOTE: Slip opinions are separately numbered (one to infinity) and are NOT consecutively numbered as one progresses from one opinion to the next. Since there were six Slip Opinions that six Justices wrote, there are thus six-page “ones”.

Part I: What the Court HELD, Exactly

[Roberts Majority Opinion, Slip Opinion p. 22, with whom Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett joined] “But we have permitted race-based admissions only within the confines of narrow restrictions. University programs must comply with strict scrutiny, they may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and—at some point—they must end. Respondents’ [Editor’s Note: meaning Harvard and UNC] admissions systems—however well intentioned [sic] and implemented in good faith—fail each of these criteria. They must therefore be invalidated under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” [footnote omitted]

[Roberts Majority Opinion, Slip Opinion p. 39] “For the reasons provided above, the Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points [sic]. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.”

[Roberts Majority Opinion, Slip Opinion p. 40] “In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race. Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice. The judgments of the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and of the District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina are reversed.”

[Thomas Concurring Opinion, Slip Opinion p. 2] “Because the Court today applies genuine strict scrutiny to the race-conscious admissions policies employed at Harvard and the University of North Carolina (UNC) and finds that they fail that searching review, I join the majority opinion in full. I write separately to offer an originalist defense of the colorblind Constitution; to explain further the flaws of the Court’s Grutter jurisprudence; to clarify that all forms of discrimination based on race—including so-called affirmative action—are prohibited under the Constitution; and to emphasize the pernicious effects of all such discrimination.”

[Gorsuch Concurring Opinion, with whom Justice Thomas also joined, Slip Opinion pp. 24-25] “The moves made in Bakke were not statutory interpretation. They were judicial improvisation. Under our Constitution, judges have never been entitled to disregard the plain terms of a valid congressional enactment based on surmise about unenacted legislative intentions. Instead, it has always been this Court’s duty ‘to give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute,’ [citation omitted] and of the Constitution itself, [citation omitted]. In this country, “[o]nly the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.” Bostock, 590 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 2). When judges disregard these principles and enforce rules “inspired only by extratextual sources and [their] own imaginations,” they usurp a lawmaking function “reserved for the people’s representatives.” Id., at ___ (slip op., at 4).

Today, the Court corrects course in its reading of the Equal Protection Clause. With that, courts should now also correct course in their treatment of Title VI. For years, they have read a solo opinion in Bakke [Editor’s Note: Justice Gorsuch is referring to Justice Powell, author of the Bakke decision, although no one joined his reasoning, but four other Justices joined in his result] like a statute while reading Title VI as a mere suggestion. A proper respect for the law demands the opposite. Title VI bears independent force beyond the Equal Protection Clause. Nothing in it grants special deference to university administrators. Nothing in it endorses racial discrimination to any degree or for any purpose. Title VI is more consequential than that.

*

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Congress took vital steps toward realizing the promise of equality under the law. As important as those initial efforts were, much work remained to be done—and much remains today. But by any measure, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 stands as a landmark on this journey and one of the Nation’s great triumphs. We have no right to make a blank sheet of any of its provisions. And when we look to the clear and powerful command Congress set forth in that law, these cases all but resolve themselves. Under Title VI, it is never permissible “‘to say “yes” to one person . . . but to say “no” to another person’” even in part “‘because of the color of his skin.’” Bakke, 438 U. S., at 418 (opinion of Stevens, J.).”

Editor’s Note: Here Justice Gorsuch sets out his opinion (above) first seen in this Concurring Opinion, with whom only Justice Thomas agrees (so it is not a “holding” of the Court), that Title VI (not Title VII) of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which both Harvard and UNC were accused of violating, is MORE strict than the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Title VI tolerates no race-based decision-making, in Justices Gorsuch and Thomas’ minds. In the Gorsuch/Thomas view, Title VI does not allow the use of race by federal grantees for any purpose, not even for a compelling reason, and even when narrowly tailored to that compelling reason.

[Kavanaugh Concurring Opinion, Slip Opinion p. 2] “I join the Court’s opinion in full. I add this concurring opinion to further explain why the Court’s decision today is consistent with and follows from the Court’s equal protection precedents, including the Court’s precedents on race-based affirmative action in higher education.”

Part II: Notable Quotes of The Justices Explaining Their Opinions

(1) Harvard Was Running A Quota System in Violation of Bakke, Gratz, Grutter, and Fisher II

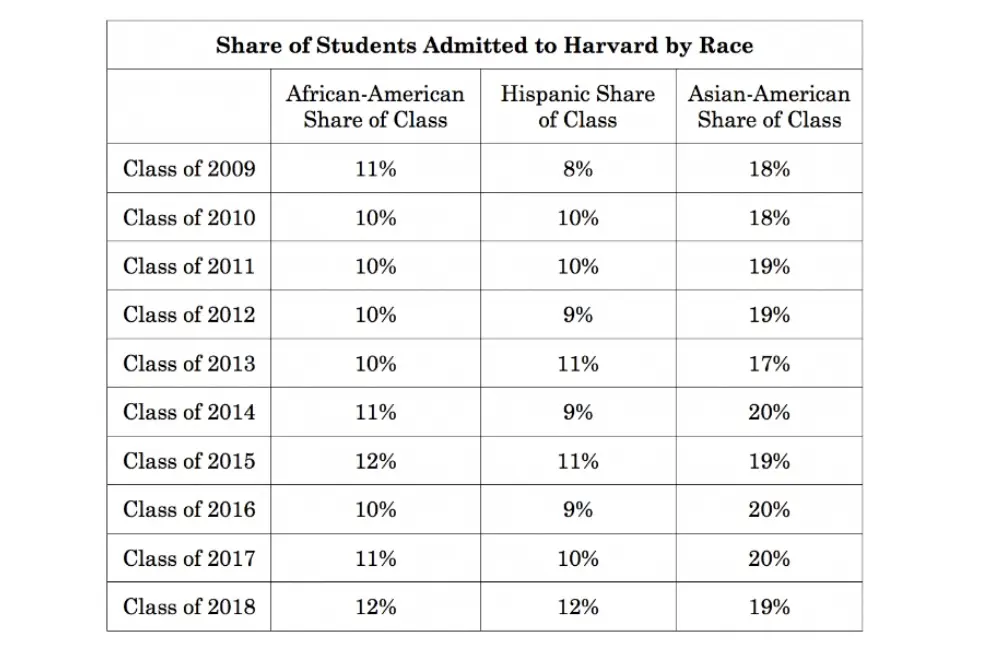

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at pp. 30-31] “Numbers all the same. At Harvard, each full committee meeting begins with a discussion of ‘how the breakdown of the class compares to the prior year in terms of racial identities.’ 397 F. Supp. 3d, at 146. And ‘if at some point in the admissions process it appears that a group is notably underrepresented or has suffered a dramatic drop off relative to the prior year, the Admissions Committee may decide to give additional attention to applications from students within that group.’ Ibid.; see also id., at 147 (District Court finding that Harvard uses race to “trac[k] how each class is shaping up relative to previous years with an eye towards achieving a level of racial diversity”); 2 App. in No. 20–1199, Cite as: 600 U. S. ____ (2023) 31 Opinion of the Court at 821–822. The results of the Harvard admissions process reflect this numerical commitment. For the admitted classes of 2009 to 2018, black students represented a tight band of 10.0%– 11.7% of the admitted pool.

The same theme held true for other minority groups: Brief for Petitioner in No. 20–1199 etc., p. 23. Harvard’s focus on numbers is obvious.” [footnote omitted] In footnote 7, Chief Justice Roberts observed that: “For all the talk of holistic and contextual judgments, the racial preferences at issue here in fact operate like clockwork.”

Editor’s Note: Chief Justice Roberts is describing a process, in his opinion, of Harvard using “plus factors” for race (which Harvard calls “tips”…meaning this “plus factor” for being Black tips you toward admission) which operate to position Black representation in the Freshman class at a roughly similar percentage, year-in and year-out.

(2) UNC Was Also Running A Quota System For African American Admissions

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 32] “UNC’s admissions program operates similarly. The University frames the challenge it faces as “the admission and enrollment of underrepresented minorities,” Brief for University Respondents in No. 21–707, at 7, a metric that turns solely on whether a group’s “percentage enrollment within the undergraduate student body is lower than their percentage within the general population in North Carolina,” 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 591, n. 7; see also Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 21–707, at 79. The University ‘has not yet fully achieved its diversity-related educational goals,’ it explains, in part due to its failure to obtain closer to proportional representation. Brief for University Respondents in No. 21–707, at 7; see also 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 594.

The problem with these approaches is well established. ‘[O]utright racial balancing’ is ‘patently unconstitutional.’ Fisher I, 570 U. S., at 311 (internal quotation marks omitted). That is so, we have repeatedly explained, because ’[a]t the heart of the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection lies the simple command that the Government must treat citizens as individuals, not as simply components of a racial, religious, sexual or national class.’ Miller, 515 U. S., at 911 [internal quotation marks omitted]. By promising to terminate their use of race only when some rough percentage of various racial groups is admitted, respondents turn that principle on its head. Their admissions programs ’effectively assure[] that race will always be relevant…and that the ultimate goal of eliminating’ race as a criterion ‘will never be achieved.’ Croson, 488 U. S., at 495 [internal quotation marks omitted].”

(3) The Law of the Fourteenth Amendment, applicable to Both Harvard and UNC, Forbids Race-Based Discrimination Absent a Compelling Interest to Do So, and The At-Issue Race-Based Practices Are “Narrowly Tailored” To Achieve that Compelling Interest

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 14] “These decisions reflect the “core purpose” of the Equal Protection Clause: ‘do[ing] away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race.’[case citation omitted]. We have recognized that repeatedly. ’The clear and central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate all official state sources of invidious racial discrimination in the States.’ [case citations omitted]. (‘The central purpose of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is the prevention of official conduct discriminating on the basis of race.’); [case citation omitted]. (‘[T]he historical fact [is] that the central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate racial discrimination.’).

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 15] “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it. And the Equal Protection Clause, we have accordingly held, applies ‘without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality’—it is ‘universal in [its] application.’ Yick Wo, 118 U. S., at 369. For ‘[t]he guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one thing when applied to one and something else when applied to a person of another color.’ Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U. S. 265, 289–290 (1978) (opinion of Powell, J.). ‘If both are not accorded the same protection, then it is not equal.’ Id., at 290. Any exception to the Constitution’s demand for equal protection must survive a daunting two-step examination known in our cases as ’strict scrutiny.’ Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, 515 U. S. 200, 227 (1995). Under that standard we ask, first, whether the racial classification is used to ‘further compelling governmental interests.’ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U. S. 306, 326 (2003). Second, if so, we ask whether the government’s use of race is ’narrowly tailored’—meaning ‘necessary’—to achieve that interest. Fisher v. University of Tex. at Austin, 570 U. S. 297, 311– 312 (2013) (Fisher I ) [internal quotation marks omitted].

Outside the circumstances of these cases, our precedents have identified only two compelling interests that permit resort to race-based government action. One is remediating specific, identified instances of past discrimination that violated the Constitution or a statute. See, e.g., Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, 551 U. S. 701, 720 (2007); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U. S. 899, 909–910 (1996); post, at 19–20, 30–31 (opinion of THOMAS, J.). The second is avoiding imminent and serious risks to human safety in prisons, such as a race riot. See Johnson v. California, 543 U. S. 499, 512–513 (2005).[footnote omitted]

(4) Past Societal Discrimination Rationale To Authorize Race-Based Discrimination Again Rejected

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 17] “Justice Powell”[Editor’s Note: author of the Bakke decision opening the door to temporary race-based admission preferences under the right circumstances] “observed the goal ‘remedying…the effects of ‘societal discrimination’” was also insufficient [to support race-based preferences in higher education admissions] because it was an ‘amorphous concept of injury that may be ageless in its reach into the past’.” Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307.

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at pp. 34-36] “The dissenting opinions resist these conclusions [that the Universities failed their proof of compliance with the ‘Strict Scrutiny’ the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause requires]. They would instead uphold respondents’ admissions programs based on their view that the Fourteenth Amendment permits state actors to remedy the effects of societal discrimination through explicitly race-based measures. Although both opinions are thorough and thoughtful in many respects, this Court has long rejected their core thesis.

The dissents’ interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause is not new. In Bakke, four Justices would have permitted race-based admissions programs to remedy the effects of societal discrimination. 438 U. S., at 362 (joint opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ., concurring in judgment in part and dissenting in part). But that minority view was just that—a minority view. Justice Powell, who provided the fifth vote and controlling opinion in Bakke, firmly rejected the notion that societal discrimination constituted a compelling interest. Such an interest presents ‘an amorphous concept of injury that may be ageless in its reach into the past,’ he explained. Id., at 307. It cannot ’justify a [racial] classification that imposes disadvantages upon persons . . . who bear no responsibility for whatever harm the beneficiaries of the [race-based] admissions program are thought to have suffered.’ Id., at 310.

The Court soon adopted Justice Powell’s analysis as its own. In the years after Bakke, the Court repeatedly held that ameliorating societal discrimination does not constitute a compelling interest that justifies race-based state action. ’[A]n effort to alleviate the effects of societal discrimination is not a compelling interest,’ we said plainly in Hunt, a 1996 case about the Voting Rights Act. 517 U. S., at 909–910. We reached the same conclusion in Croson, a case that concerned a preferential government contracting program. Permitting ’past societal discrimination’ to ’serve as the basis for rigid racial preferences would be to open the door to competing claims for ‘remedial relief ’ for every disadvantaged group.’ 488 U. S., at 505. Opening that door would shutter another—’[t]he dream of a Nation of equal citizens . . . would be lost,’ we observed, ‘in a mosaic of shifting preferences based on inherently unmeasurable claims of past wrongs.’ Id., at 505–506. ‘[S]uch a result would be contrary to both the letter and spirit of a constitutional provision whose central command is equality.’ Id., at 506.

The dissents here do not acknowledge any of this. They fail to cite Hunt. They fail to cite Croson. They fail to mention that the entirety of their analysis of the Equal Protection Clause—the statistics, the cases, the history—has been considered and rejected before. There is a reason the principal dissent must invoke Justice Marshall’s partial dissent in Bakke nearly a dozen times while mentioning Justice Powell’s controlling opinion barely once (JUSTICE JACKSON’s opinion ignores Justice Powell altogether). For what one dissent denigrates as ’rhetorical flourishes about colorblindness,’ post, at 14 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.), are in fact the proud pronouncements of cases like Loving [striking down prohibitions on inter-racial marriage] and Yick Wo [an 1886 case decision striking down under the Fourteenth Amendment the manner in which the city of San Francisco denied permits for waivers of a neutral city ordinance requiring laundries to be made of stone or brick but disproportionately denied waivers to Chinese applicants], like Shelley [striking down under the Fourteenth Amendment a St. Louis ordinance restricting African Americans and Mongolians from occupying property they had purchased in the city limits] and Bolling [school segregation was unlawful under the Fifth Amendments Equal Protection Component] —they are defining statements of law. We understand the dissents want that law to be different. They are entitled to that desire. But they surely cannot claim the mantle of stare decisis while pursuing it. [fn 8 omitted here but discussed elsewhere]

The dissents are no more faithful to our precedent on race-based admissions. To hear the principal dissent tell it, Grutter blessed such programs indefinitely, until ‘racial inequality will end.’ Post, at 54 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.). But Grutter did no such thing. It emphasized—not once or twice, but at least six separate times—that race-based admissions programs ‘must have reasonable durational limits’ and that their ‘deviation from the norm of equal treatment’ must be ’a temporary matter.’ 539 U. S., at 342. The Court also disclaimed ‘[e]nshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences.” Ibid. Yet the justification for race-based admissions that the dissent latches on to is just that—unceasing.’

(5) Constitutional Law Before Grutter Had Allowed Only State-Sponsored Race-Based Discrimination For Two Reasons

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 20] “These limits [on race-based admissions practices], Grutter explained, were intended to guard against two dangers that all race-based government action portends. The first is the risk that the use of race will devolve into ’illegitimate . . . stereotyp[ing].’ Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co., 488 U. S. 469, 493 (1989) (plurality opinion). Universities were thus not permitted to operate their admissions programs on the ‘belief that minority students always (or even consistently) express some characteristic minority viewpoint on any issue.’ Grutter, 539 U. S., at 333 [internal quotation marks omitted]. The second risk is that race would be used not as a plus, but as a negative—to discriminate against those racial groups that were not the beneficiaries of the race-based preference. A university’s use of race, accordingly, could not occur in a manner that ’unduly harm[ed] nonminority applicants.’ Id., at 341.

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 38] Chief Justice Roberts accused the Dissent of trying to position “a judiciary that picks winners and losers based on the color of their skin. While the dissent would certainly not permit university programs that discriminated against black and Latino applicants, it is perfectly willing to let the programs here continue. In its view, this Court is supposed to tell state actors when they have picked the right races to benefit. Separate but equal is ‘inherently unequal,’ said Brown [v. Board of Education]. 347 U. S., at 495 (emphasis added). It depends, says the dissent.

That is a remarkable view of the judicial role—remarkably wrong. Lost in the false pretense of judicial humility that the dissent espouses is a claim to power so radical, so destructive, that it required a Second Founding to undo. ’Justice Harlan knew better,’ one of his dissents decrees. Post, at 5 (opinion of JACKSON, J.). Indeed he did: ‘[I]n view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.’ Plessy, 163 U. S., at 559 (Harlan, J., dissenting).

(6) The Use of Race-Based Discrimination in Favor of Black Admission Candidates to Higher Education Was Always Only Temporary

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 21] ”To manage these concerns, Grutter imposed one final limit on race-based admissions programs. At some point, the Court held, they must end. Id., at 342. This requirement was critical, and Grutter emphasized it repeatedly. ‘[A]ll race-conscious admissions programs [must] have a termination point’; they ‘must have reasonable durational limits’; they ‘must be limited in time’; they must have ‘sunset provisions’; they ‘must have a logical end point’ [sic]; their ‘deviation from the norm of equal treatment’ must be ‘a temporary matter.’ Ibid. [internal quotation marks omitted]. The importance of an end point [sic] was not just a matter of repetition. It was the reason the Court was willing to dispense temporarily with the Constitution’s unambiguous guarantee of equal protection. The Court recognized as much: ’[e]nshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences,’ the Court explained, ’would offend this fundamental equal protection principle.’ Ibid.; see also id., at 342–343 (quoting N. Nathanson & C. Bartnik, The Constitutionality of Preferential Treatment for Minority Applicants to Professional Schools, 58 Chi. Bar Rec. 282, 293 (May–June 1977), for the proposition that ’[i]t would be a sad day indeed, were America to become a quota-ridden society, with each identifiable minority assigned proportional representation in every desirable walk of life’).

Grutter thus concluded with the following caution: ‘It has been 25 years since Justice Powell first approved the use of race to further an interest in student body diversity in the context of public higher education. . . . We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.’” 539 U. S., at 343.

[Kavanaugh Concurring Slip Op at pp. 2-3] “In 2003, 25 years after Bakke, five Members of this Court again held that race-based affirmative action in higher education did not violate the Equal Protection Clause or Title VI. Grutter, 539 U. S., at 343. This time, however, the Court also specifically indicated—despite the reservations of Justice Ginsburg and Justice Breyer—that race-based affirmative action in higher education would not be constitutionally justified after another 25 years, at least absent something not ‘expect[ed].’ Ibid. And various Members of the Court wrote separate opinions explicitly referencing the Court’s 25-year limit.

- Justice O’Connor’s opinion for the Court stated: ‘We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.’ Ibid.

- Justice Thomas expressly concurred in ‘the Court’s holding that racial discrimination in higher education admissions will be illegal in 25 years.’ Id., at 351 (opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part).

- Justice Thomas, joined here by Justice Scalia, reiterated ‘the Court’s holding’ that race-based affirmative action in higher education ‘will be unconstitutional in 25 years’ and ‘that in 25 years the practices of the Law School will be illegal,’ while also stating that ‘they are, for the reasons I have given, illegal now.’ Id., at 375–376.

- Justice Kennedy referred to ’the Court’s pronouncement that race-conscious admissions programs will be unnecessary 25 years from now.’ Id., at 394 (dissenting opinion).

- Justice Ginsburg, joined by Justice Breyer, acknowledged the Court’s 25-year limit but questioned it, writing that ‘one may hope, but not firmly forecast, that over the next generation’s span, progress toward nondiscrimination and genuinely equal opportunity will make it safe to sunset affirmative action.’ Id., at 346 (concurring opinion).

In allowing race-based affirmative action in higher education for another generation—and only for another generation—the Court in Grutter took into account competing considerations. The Court recognized the barriers that some minority applicants to universities still faced as of 2003, notwithstanding the progress made since Bakke. See Grutter, 539 U. S., at 343. The Court stressed, however, that’“there are serious problems of justice connected with the idea of preference itself.’ Id., at 341 [internal quotation marks omitted]. And the Court added that a ‘core purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to do away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race.’ Ibid. [internal quotation marks omitted].

The Grutter Court also emphasized the equal protection principle that racial classifications, even when otherwise permissible, must be a ‘temporary matter,’ and ’must be limited in time.’ Id., at 342 (quoting Croson, 488 U. S., at 510 (plurality opinion of O’Connor, J.)). The requirement of a time limit ‘reflects that racial classifications, however compelling their goals, are potentially so dangerous that they may be employed no more broadly than the interest demands. Enshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences would offend this fundamental equal protection principle.’ Grutter, 539 U. S., at 342. Importantly, the Grutter Court saw ’no reason to exempt race-conscious admissions programs from the requirement that all governmental use of race must have a logical end point.’ [sic] Ibid. The Court reasoned that the ‘requirement that all race-conscious admissions programs have a termination point assures all citizens that the deviation from the norm of equal treatment of all racial and ethnic groups is a temporary matter, a measure taken in the service of the goal of equality itself.’ Ibid. [internal quotation marks and alteration omitted]. The Court therefore concluded that race-based affirmative action programs in higher education, like other racial classifications, must be ‘limited in time.’ Ibid.

The Grutter Court’s conclusion that race-based affirmative action in higher education must be limited in time followed not only from fundamental equal protection principles, but also from this Court’s equal protection precedents applying those principles. Under those precedents, racial classifications may not continue indefinitely. For example, in the elementary and secondary school context after Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the Court authorized race-based student assignments for several decades—but not indefinitely into the future. [citations omitted].

In those decisions, this Court ruled that the race-based ‘injunctions entered in school desegregation cases’ could not ‘operate in perpetuity.’ Dowell, 498 U. S., at 248. Consistent with those decisions, the Grutter Court ruled that race-based affirmative action in higher education likewise could not operate in perpetuity. As of 2003, when Grutter was decided, many race-based affirmative action programs in higher education had been operating for about 25 to 35 years. Pointing to the Court’s precedents requiring that racial classifications be ‘temporary,’ Croson, 488 U. S., at 510 (plurality opinion of O’Connor, J.), the petitioner in Grutter, joined by the United States, argued that race-based affirmative action in higher education could continue no longer. See Brief for Petitioner 21–22, 30–31, 33, 42, Brief for United States 26–27, in Grutter v. Bollinger, O. T. 2002, No. 02–241.

The Grutter Court rejected those arguments for ending race-based affirmative action in higher education in 2003. But in doing so, the Court struck a careful balance. The Court ruled that narrowly tailored race-based affirmative action in higher education could continue for another generation. But the Court also explicitly rejected any ’permanent justification for racial preferences,’ and therefore ruled that race-based affirmative action in higher education could continue only for another generation. 539 U. S., at 342–343.

Harvard and North Carolina would prefer that the Court now ignore or discard 25-year limit on race-based affirmative action in higher education, or treat it as a mere aspiration. But the 25-year limit constituted an important part of Justice O’Connor’s nuanced opinion for the Court in Grutter. Indeed, four of the separate opinions in Grutter discussed the majority opinion’s 25-year limit, which belies any suggestion that the Court’s reference to it was insignificant or not carefully considered. In short, the Court in Grutter expressly recognized the serious issues raised by racial classifications—particularly permanent or long-term racial classifications. And the Court ‘assure[d] all citizens’ throughout America that ‘the deviation from the norm of equal treatment’ in higher education could continue for another generation, and only for another generation. Ibid. [internal quotation marks omitted].

A generation has now passed since Grutter, and about 50 years have gone by since the era of Bakke and DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U. S. 312 (1974), when race-based affirmative action programs in higher education largely began. In light of the Constitution’s text, history, and precedent, the Court’s decision today appropriately respects and abides by Grutter’s explicit temporal limit on the use of race-based affirmative action in higher education.”

(7) Neither Harvard of UNC Had Sunset Dates Necessary To Sustain Their Discriminatory Race-Based School Admission Practices

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 22] “Twenty years later [after Grutter], no end is in sight. ‘Harvard’s view about when [race-based admissions will end] doesn’t have a date on it.’ Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 20–1199, p. 85; Brief for Respondent in No. 20–1199, p. 52. Neither does UNC’s. 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 612. Yet both insist that the use of race in their admissions programs must continue. But we have permitted race-based admissions only within the confines of narrow restrictions. University programs must comply with strict scrutiny, they may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and—at some point—they must end. Respondents’ admissions systems—however well intentioned [sic] and implemented in good faith—fail each of these criteria. They must therefore be invalidated under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” [footnote omitted]

(8) One of The Dissenters Realizing That Equal Protection Clause’s “Strict Scrutiny” Requirements Condemn Race-Based Discrimination in Higher Education Admissions Decisions Advocated Eliminating 200 Years of Constitutional Law To Just Eliminate The Strict Scrutiny Requirement

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 26, footnote 5] [Editor’s Note: The gloves came off a little bit here.] “For that reason [that the universities could not satisfy the demands of ‘Strict Scrutiny’], one dissent candidly advocates abandoning the demands of strict scrutiny. See post, at 24, 26–28 (opinion of JACKSON, J.) (arguing the Court must ‘get out of the way,’ ‘leav[e] well enough alone,’ and defer to universities and ‘experts’ in determining who should be discriminated against). An opinion professing fidelity to history (to say nothing of the law) should surely see the folly in that approach.”

(9) The Universities Used Race-Based Decision As A “Negative” That Grutter Condemned Since Admissions To Limited Undergraduate Programs With Limited Seats Was a “Zero-Sum” Game

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at p. 27] “The race-based admissions systems that respondents employ also fail to comply with the twin commands of the Equal Protection Clause that race may never be used as a ‘negative’ and that it may not operate as a stereotype.

First, our cases have stressed that an individual’s race may never be used against him in the admissions process. Here, however, the First Circuit found that Harvard’s consideration of race has led to an 11.1% decrease in the number of Asian-Americans [sic] admitted to Harvard. 980 F. 3d, at 170, n. 29. And the District Court observed that Harvard’s ‘policy of considering applicants’ race . . . overall results in fewer Asian American and white students being admitted.’ 397 F. Supp. 3d, at 178.

* * * * *

College admissions are zero-sum. A benefit provided to some applicants but not to others necessarily advantages the former group at the expense of the latter.”

(10) The University’s Arguments That Their Use of Race Was Not “Negative” Because Their Use Did Not Adversely Affect Many Asians or Whites Was Factually False When Compared To The Trial Record

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at pp. 27-28] “Respondents [the Universities] also suggest that race is not a negative factor because it does not impact many admissions decisions. See id., at 49; Brief for University Respondents in No. 21– 707 [UNC], at 2. Yet, at the same time, respondents also maintain that the demographics of their admitted classes would meaningfully change if race-based admissions were abandoned. And they acknowledge that race is determinative for at least some—if not many—of the students they admit. See, e.g., Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 20–1199, at 67; 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 633. How else but ‘negative’ can race be described if, in its absence, members of some racial groups would be admitted in greater numbers than they otherwise would have been? The ‘[e]qual protection of the laws is not achieved through indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.’ Shelley, 334 U. S., at 22.” [Footnote 6 goes here]

This is footnote 6: “JUSTICE JACKSON contends that race does not play a ‘determinative role for applicants’ to UNC. Post, at 24. But even the principal dissent acknowledges that race—and race alone—explains the admissions decisions for hundreds if not thousands of applicants to UNC each year. Post, at 33, n. 28 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.); see also Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of N. C. at Chapel Hill, No. 1:14–cv–954 (MDNC, Dec. 21, 2020), ECF Doc. 233, at 23–27 (UNC expert testifying that race explains 1.2% of in state [sic] and 5.1% of out of state admissions decisions); 3 App. in No. 21–707, at 1069 (observing that UNC evaluated 57,225 in state [sic applicants and 105,632 out of state applicants from 2016–2021). The suggestion by the principal dissent that our analysis relies on extra-record materials, see post, at 29–30, n. 25 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.), is simply mistaken.”

[Gorsuch Concurring Opinion Slip Op at pp. 9 &10]

Harvard: Harvard’s entering Freshman undergraduate class has “roughly 1,600 spots.” “’At least 10% of Harvard’s admitted class . . . would most likely not be admitted in the absence of Harvard’s race-conscious admissions process.’ Ibid. [Editor’s Note: 10% x 1600=160 race-based admissions of students who otherwise would not have been admitted in the normal course.] Race-based tips are ‘determinative’ in securing favorable decisions for a significant percentage of ‘African American and Hispanic applicants,’ the ‘primary beneficiaries’ of this system. Ibid. There are clear losers too. ‘[W]hite and Asian American applicants are unlikely to receive a meaningful race-based tip,’ id., at 190, n. 56, and ‘overall’ the school’s race-based practices ‘resul[t] in fewer Asian American and white students being admitted,’ id., at 178. For these reasons and others still, the district court concluded that ‘Harvard’s admissions process is not facially neutral’ with respect to race. Id., at 189–190; see also id., at 190, n. 56 (‘The policy cannot . . . be considered facially neutral from a Title VI perspective.’).”

UNC: “Things work similarly at UNC. In a typical year, about 44,000 applicants vie for 4,200 spots. 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 595. Admissions officers read each application and rate prospective students along eight dimensions: academic programming, academic performance, standardized tests, extracurriculars, special talents, essays, background, and personal. Id., at 600. The district court found that ‘UNC’s., concurring admissions policies mandate that race is taken into consideration’ in this process as a “‘plus’ facto[r].” Id., at 594– 595. It is a plus that is ‘sometimes’ awarded to ‘underrepresented minority’ or ’URM’ candidates—a group UNC defines to include “‘those students identifying themselves as African American or [B]lack; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Hispanic, Latino, or Latina,’” but not Asian or white students. Id., at 591–592, n. 7, 601.

At UNC, the admissions officers’ decisions to admit or deny are “‘provisionally final.’” Ante, at 4 (opinion for the Court). The decisions become truly final only after a committee approves or rejects them. 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 599. That committee may consider an applicant’s race too. Id., at 607. In the end, the district court found that ’race plays a role’—perhaps even ‘a determinative role’—in the decision to admit or deny some ‘URM students.’ Id., at 634; see also id., at 662 (“race may tip the scale”). Nor is this an accident. As at Harvard, officials at UNC have made a ‘deliberate decision’ to employ race-conscious admissions practices. Id., at 588–589.

While the district courts’ findings tell the full story, one can also get a glimpse from aggregate statistics. Consider the chart in the Court’s opinion collecting Harvard’s data for the period 2009 to 2018. Ante, at 31. The racial composition of each incoming class remained steady over that time—remarkably so. The proportion of African Americans hovered between 10% and 12%; the proportion of Hispanics between 8% and 12%; and the proportion of Asian Americans between 17% and 20%. Ibid. Might this merely reflect the demographics of the school’s applicant pool? Cf. post, at 35 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.). Perhaps—at least assuming the applicant pool looks much the same each year and the school rather mechanically admits applicants based on objective criteria. But the possibility that it instead betrays the school’s persistent focus on numbers of this race and numbers of that race is entirely consistent with the findings recounted above. See, e.g., 397 F. Supp. 3d, at 146 (“if at some point in the admissions process it appears that a group is notably underrepresented or has suffered a dramatic drop off relative to the prior year, the [committee] may decide to give additional attention to applications from students within that group”); cf. ante, at 31–32, n. 7 (opinion for the Court).”

(11) The University Race-Based Admissions were Also Infirm Because They Relied On Racial Stereotypes Of Blacks That Grutter Forbade

[Roberts Majority Slip Op at pp. 28-30] “Respondents’ [universities] admissions programs are infirm for a second reason as well. We have long held that universities may not operate their admissions programs on the ’belief that minority students always (or even consistently) express some characteristic minority viewpoint on any issue.’ Grutter, 539 U. S., at 333 [internal quotation marks omitted]. That requirement is found throughout our Equal Protection Clause jurisprudence more generally. See, e.g., Schuette v. BAMN, 572 U. S. 291, 308 (2014) (plurality opinion) (‘In cautioning against ‘impermissible racial stereotypes,’ this Court has rejected the assumption that ‘members of the same racial group—regardless of their age, education, economic status, or the community in which they live—think alike . . . .’’ (quoting Shaw v. Reno, 509 U. S 600 U. S. ____ (2023) Opinion of the Court 630, 647 (1993)).

Yet by accepting race-based admissions programs in which some students may obtain preferences on the basis of race alone, respondents’ programs tolerate the very thing that Grutter foreswore: stereotyping. The point of respondents’ admissions programs is that there is an inherent benefit in race qua race—in race for race’s sake. Respondents admit as much. Harvard’s admissions process rests on the pernicious stereotype that “a black student can usually bring something that a white person cannot offer.” Bakke, 438 U. S., at 316 (opinion of Powell, J.) [internal quotation marks omitted]; see also Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 20–1199, at 92. UNC is much the same. It argues that race in itself “says [something] about who you are.” Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 21–707, at 97; see also id., at 96 (analogizing being of a certain race to being from a rural area).

We have time and again forcefully rejected the notion that government actors may intentionally allocate preference to those “who may have little in common with one another but the color of their skin.” Shaw, 509 U. S., at 647. The entire point of the Equal Protection Clause is that treating someone differently because of their skin color is not like treating them differently because they are from a city or from a suburb, or because they play the violin poorly or well.

’One of the principal reasons race is treated as a forbidden classification is that it demeans the dignity and worth of a person to be judged by ancestry instead of by his or her own merit and essential qualities.’ Rice, 528 U. S., at 517. But when a university admits students ‘on the basis of race, it engages in the offensive and demeaning assumption that [students] of a particular race, because of their race, think alike,’ Miller v. Johnson, 515 U. S. 900, 911–912 (1995) [internal quotation marks omitted]—at the very least alike in the sense of being different from nonminority students. In doing so, the university furthers ‘stereotypes that treat individuals as the product of their race, evaluating their thoughts and efforts—their very worth as citizens—according to a criterion barred to the Government by history and the Constitution.’ Id., at 912 [internal quotation marks omitted]. Such stereotyping can only ’cause[] continued hurt and injury,’ Edmonson, 500 U. S., at 631, contrary as it is to the ‘core purpose’ of the Equal Protection Clause, Palmore, 466 U. S., at 432.”

(12) The Dissenting Opinions

(Justices Sotomayor, Jackson, and Kagan hammered home social policy arguments to support race-based decision-making. They supported their arguments in favor of race-based decision-making in higher education school admissions by referencing the continuing plight of African Americans. Specifically, they pointed out that many African Americans are still struggling to overcome a history of slavery, segregation, poverty, and unequal access to education.)

Justice Sotomayor (with whom Justice Jackson (as to UNC) and Justice Kagan joined) dissenting: [Sotomayor Dissenting Slip Op at pp. 1-2 ] “The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment enshrines a guarantee of racial equality. The Court long ago concluded that this guarantee can be enforced through race-conscious means in a society that is not, and has never been, colorblind. In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the Court recognized the constitutional necessity of racially integrated schools in light of the harm inflicted by segregation and the ‘importance of education to our democratic society.’ Id., at 492–495. For 45 years, the Court extended Brown’s transformative legacy to the context of higher education, allowing colleges and universities to consider race in a limited way and for the limited purpose of promoting the important benefits of racial diversity. This limited use of race has helped equalize educational opportunities for all students of every race and background and has improved racial diversity on college campuses. Although progress has been slow and imperfect, race-conscious college admissions policies have advanced the Constitution’s guarantee of equality and have promoted Brown’s vision of a Nation with more inclusive schools.

Today, this Court stands in the way and rolls back decades of precedent and momentous progress. It holds that race can no longer be used in a limited way in college admissions to achieve such critical benefits. In so holding, the Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter. The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society. Because the Court’s opinion is not grounded in law or fact and contravenes the vision of equality embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment, I dissent.”

Justice Jackson (with whom Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan join)

[Jackson Dissenting Slip Op at pp. 1-2 as to the UNC decision] “Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations. Every moment these gaps persist is a moment in which this great country falls short of actualizing one of its foundational principles—the ’self-evident’ truth that all of us are created equal. Yet, today, the Court determines that holistic admissions programs like the one that the University of North Carolina (UNC) has operated, consistent with Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U. S. 306 (2003), are a problem with respect to achievement of that aspiration, rather than a viable solution (as has long been evident to historians, sociologists, and policymakers alike).”

Editor’s Note: A new era now begins with the country facing the same problems before last week’s Harvard and UNC case decision. Where to now?

Note to the Federal Contractor Community:

Federal contractors know that OFCCP’s “Affirmative Action” requirements do not require race-based, or national origin-based, or sex-based preferences in employment. But because of provocative attention-grabbing mainstream media reporting, federal contractor representatives and their vendors now suddenly live under an unfortunate and unearned cloud of suspicion that they are daily engaging in unlawful preferential race-based and/or national-origin-based or sex-based “Affirmative Action.”

View the four “Elevator Speeches” federal contractors and their AAP vendors ought to commit to memory, or ones like these, and repeat often in the coming weeks and months to set the record straight.

THIS COLUMN IS MEANT TO ASSIST IN A GENERAL UNDERSTANDING OF THE CURRENT LAW AND PRACTICE RELATING TO OFCCP. IT IS NOT TO BE REGARDED AS LEGAL ADVICE. COMPANIES OR INDIVIDUALS WITH PARTICULAR QUESTIONS SHOULD SEEK ADVICE OF COUNSEL.

SUBSCRIBE.

Compliance Alerts

Compliance Tips

Week In Review (WIR)

Subscribe to receive alerts, news and updates on all things related to OFCCP compliance as it applies to federal contractors.

OFCCP Compliance Text Alerts

Get OFCCP compliance alerts on your cell phone. Text the word compliance to 55678 and confirm your subscription. Provider message and data rates may apply.